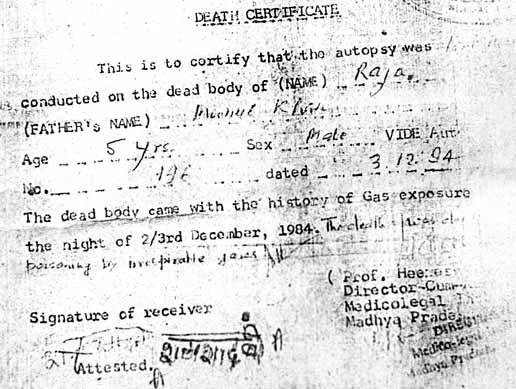

| On the night of 2nd - 3rd December

1984,40 tones of methyl iso cyanate and other lethal gases leaked

from Union Carbides Bhopal Factory. This remains the worst industrial

accident ever. It is estimated that 8,000 people died in the immediate

aftermath, that the death toll to date is 16,000 and that 500,000

people's health has been adversely effected. The "gas effected"

people of Bhopal still fight for justice and compensation.

{top}

Since 1984 the Western World seems either

to have forgotten Bhopal, or the name has become an abstract symbol

in the same way that Dunblane and Lockerbie have. In India ecological

disasters are often labelled"mini-Bhopals" or "the

next Bhopal". In Bhopal the survivors harbour anger and resentment

mainly for the way in which they have been treated by their government

and Union Carbide since the disaster as well as for the disaster

itself.

The gas spread through the slums and poor

suburbs, which are clustered around the factory. If it had made

it across the vast lakes to New Bhopal and the affluent end of town

things may have turned out differently however, many unaffected

people now think that the survivors should stop moaning and move

on. As it stands, most of the survivors have received about £350

(Rs 25,000) in compensation from Union Carbide, about half of which

has been deducted to repay earlier government relief. This leaves

many of the survivors badly in debt having sold their homes and

possessions to cover medical expenses.

{top}

The medical legacy of the disaster continues.

A medical survey conducted between 1987 and 1991 showed that there

was a threefold increase in the number of people with respiratory

symptoms. As well as asthma, recurrent chest infections and fibrosis

of the lungs the prevalence of pulmonary chest infection is more

than three times the national average. There is a host of other

lasting medical and psychiatric problems associated with surviving

the disaster including eye damage, joint pain and post-traumatic

stress disorder.

{top}

The full extent of these symptoms is not

known since medical research was terminated in 1994. These problems

are compounded because government doctors have never kept medical

records on people seeking help. In fact they have been seriously

criticised for using inappropriate drugs to provide short-term relief

and ignoring long-term treatment of chronic illnesses. The government

has built several new hospitals. The largest (the Kamala Nehru hospital)

is still not completed and despite being started in 1987 has not

treated a single gas victim. During it's construction the cost of

the Kamala Nehru hospital has tripled and survivors groups have

made accusations of profiteering and corruption.

Stories of corruption within the government

hospital system are common and usually concern doctors who refuse

to see patients admitted unless they turn up for their private clinics.

One woman said that she had to pay a large bribe to a doctor to

see her father after he had lain comatose in a hospital bed for

two weeks without being examined. Many families have had to sell

everything that they own in order meet large medical expenses.

{top}

It was in response to the government's

appallingly chaotic medical response that the Sambhavna Trust clinic

was opened in 1996. It offers a choice of conventional or ayurvedic

treatment as well as massage and yoga therapies. Unlike the government

hospitals keep detailed records on each patient and constantly evaluate

the effectiveness of all the treatments they offer. The Trust raises

money from private donation and refuses corporate donations.

{top}

Union Carbide's response to the disaster

was denial. After failing to raise the alarm once the MIC leak had

been detected, Union Carbide then declared that the gas was "like

tear gas" and that "you apply water [to the eyes] and

you get relief". A few days later, even after the death toll

topped 8,000 people, a Union Carbide representative was quoted as

saying that the gas was "nothing more than a potent tear gas".

Doctors associated with Union Carbide pump out misinformation, attempting

to hide any evidence that the effects of exposure to the gas were

permanent.

{top}

In the years that followed Union Carbide

did everything they could to play down what had happened and to

escape criminal charges and payment of compensation. The Indian

government, on behalf of the victims, filed a suit for 3 billion

US dollars but eventual settled for only 470 million US dollars.

In return criminal charges against the corporation would be dropped

and the Indian government would defend any other suits filed against

Union Carbide. With the amount of people involved this level of

compensation is less than the Indian government standard for railway

accidents.

On appeal in 1991 the Supreme Court (the

highest court in India) ruled that the amount of compensation would

stand but in addition Union Carbide must build a 500-bed hospital.

It also revoked the corporation's immunity from prosecution and

charges of culpable homicide were reinstated. In 1992 after the

failure of Union Carbide's representatives, including Warren Anderson,

to respond to numerous summonses, Bhopal District Court froze the

parent companies shares in the Indian subsidiary.

{top}

The response of Union Carbide was to create

the Bhopal Hospital Trust (BHT) to build the hospital. Despite a

Bhopal Court ruling that money for the hospital should come from

Union Carbide itself the Supreme Court allowed the BHT to receive

the money from the sale of the subsidiary shares. Union Carbide

itself only donated one thousand pounds to initiate the BHT and

now free from punitive measures has continued to ignore summonses.

{top}

The BHT's health care plans have been seriously

criticised by several medical bodies and survivors groups have questioned

the sense of building another hospital in a city that probably has

more hospital beds per head of population than any other city in

the world. These survivors groups are also concerned that a company

previously engaged in chemical and biological warfare research should

be permitted to run a ten-bed research unit in the hospital, especially

considering that there is no undertaking to release findings. While

the hospital was under construction the building site was raided

by labour officials who found that child labourers, as young as

nine years old, were being employed.

{top}

Today the decaying the Union Carbide factory

remains abandoned and decaying, even the slums that were upwind

from the factory on the night of the disaster are now being effected.

Toxic material, released as the factory decays, has entered the

ground water use by the slums for washing, cooking and drinking.

The site in now owned by the state government who have recently

been searching for a way to redevelop the area. One suggestion that

surfaced and was quickly condemned by activists was to build a theme

park to attract tourists.

{top}

Another disturbing legacy of the Bhopal

disaster has appeared recently. When DuPont were negotiating with

the Indian government over plans to build a nylon factory in Goa,

they insisted that the parent company would not be liable for any

industrial disaster that may befall the Indian subsidiary.

|